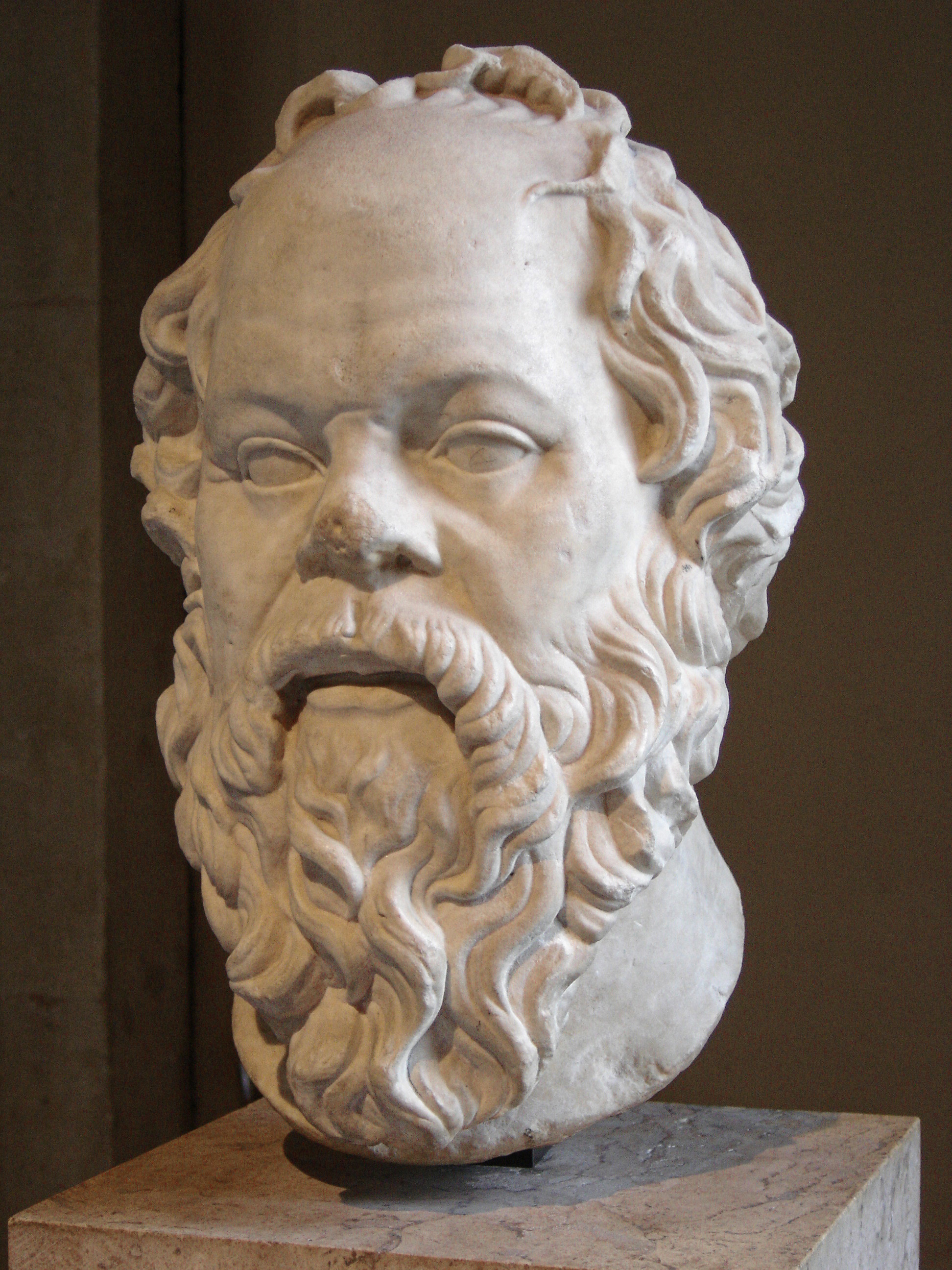

"Socrates is one of the few individuals whom one could say has so-shaped the cultural and intellectual development of the world that, without him, history would be profoundly different. He is best known for his association with the Socratic method of question and answer, his claim that he was ignorant (or aware of his own absence of knowledge), and his claim that the unexamined life is not worth living, for human beings. He was the inspiration for Plato, the thinker widely held to be the founder of the Western philosophical tradition."

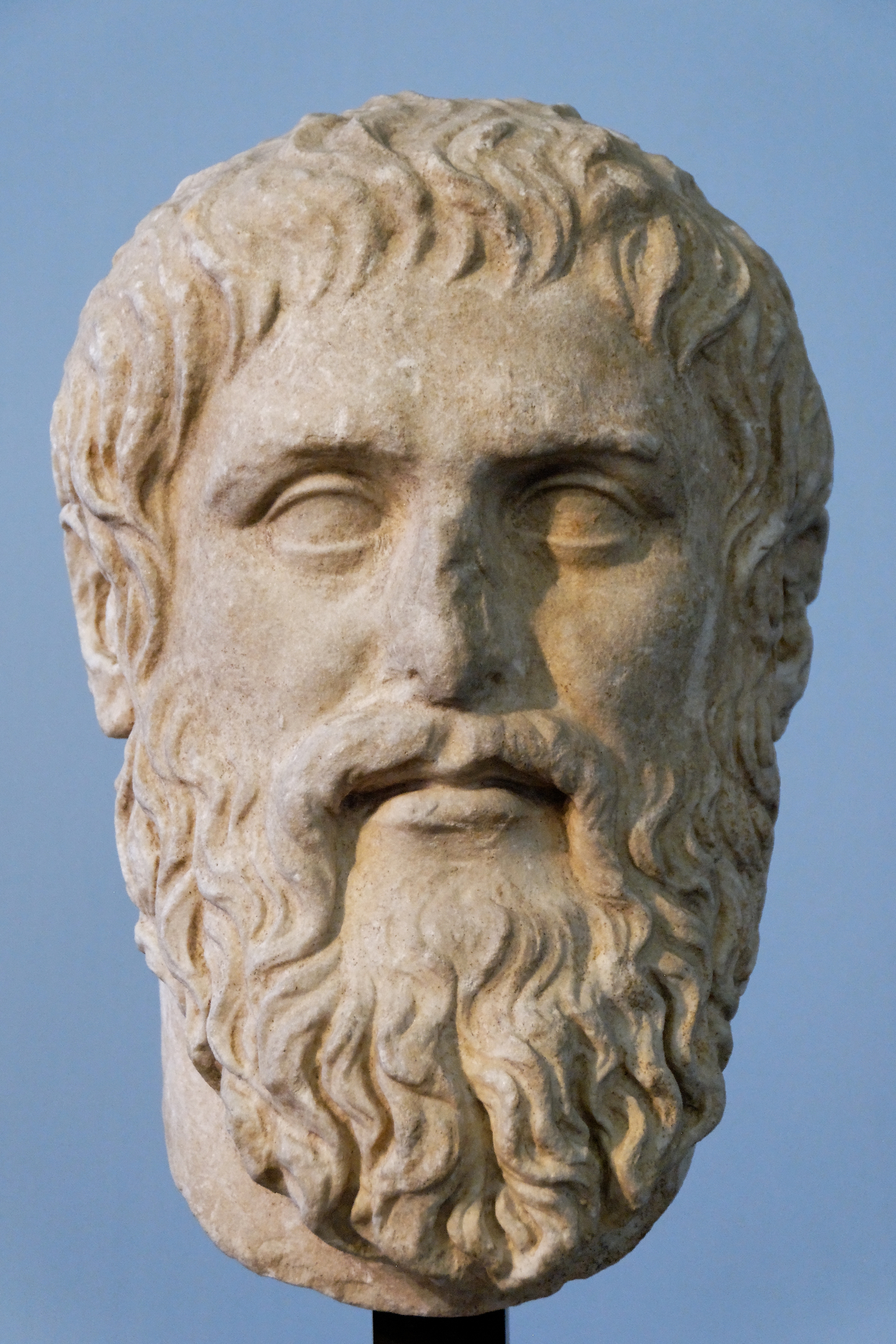

"Plato (429?–347 B.C.E.) is, by any reckoning, one of the most dazzling writers in the Western literary tradition and one of the most penetrating, wide-ranging, and influential authors in the history of philosophy. An Athenian citizen of high status, he displays in his works his absorption in the political events and intellectual movements of his time, but the questions he raises are so profound and the strategies he uses for tackling them so richly suggestive and provocative that educated readers of nearly every period have in some way been influenced by him, and in practically every age there have been philosophers who count themselves Platonists in some important respects. He was not the first thinker or writer to whom the word “philosopher” should be applied. But he was so self-conscious about how philosophy should be conceived, and what its scope and ambitions properly are, and he so transformed the intellectual currents with which he grappled, that the subject of philosophy, as it is often conceived—a rigorous and systematic examination of ethical, political, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, armed with a distinctive method—can be called his invention. Few other authors in the history of Western philosophy approximate him in depth and range: perhaps only Aristotle (who studied with him), Aquinas, and Kant would be generally agreed to be of the same rank."

"Metaphysics, then, studies the ways in which anything that is can be said or thought to be. Leaving to sciences like biology or physics or mathematics or psychology the task of addressing the special ways in which physical things, or living things, or mathematical objects, e.g., numbers, or souls (minds) come to have the peculiar qualities each, respectively, has, the subject-matter of metaphysics are principles common to everything. Perhaps the most general principle is: to be is to be something. Nothing just exists, we might say. This notion implies that each entity/item/thing has at least some one feature or quality or property. Keeping at a general level, we can provisionally distinguish three factors involved when anything is whatever it is: there is that which bears or has the property, often called the ‘subject’, e.g., Socrates, the number three, or my soul; there is the property which is possessed; e.g., being thin, being odd, and being immortal; and there is the manner or way in which the property is tied or connected to the subject. For instance, while Socrates may be accidentally thin, since he can change, that is, gain and lose weight, three cannot fail to be odd nor, if Plato is correct, can the soul fail to be immortal. The metaphysician, then, considers physical or material things as well as immaterial items such as souls, god and numbers in order to study notions like property, subject, change, being essentially or accidentally."

Plato's Ethics and Politics in The Republic

"Plato’s Republic centers on a simple question: is it always better to be just than unjust? The puzzles in Book One prepare for this question, and Glaucon and Adeimantus make it explicit at the beginning of Book Two. To answer the question, Socrates takes a long way around, sketching an account of a good city on the grounds that a good city would be just and that defining justice as a virtue of a city would help to define justice as a virtue of a human being. Socrates is finally close to answering the question after he characterizes justice as a personal virtue at the end of Book Four, but he is interrupted and challenged to defend some of the more controversial features of the good city he has sketched. In Books Five through Seven, he addresses this challenge, arguing (in effect) that the just city and the just human being as he has sketched them are in fact good and are in principle possible. After this long digression, Socrates in Books Eight and Nine finally delivers three “proofs” that it is always better to be just than unjust. Then, because Socrates wants not only to show that it is always better to be just but also to convince Glaucon and Adeimantus of this point, and because Socrates’ proofs are opposed by the teachings of poets, he bolsters his case in Book Ten by indicting the poets’ claims to represent the truth and by offering a new myth that is consonant with his proofs."